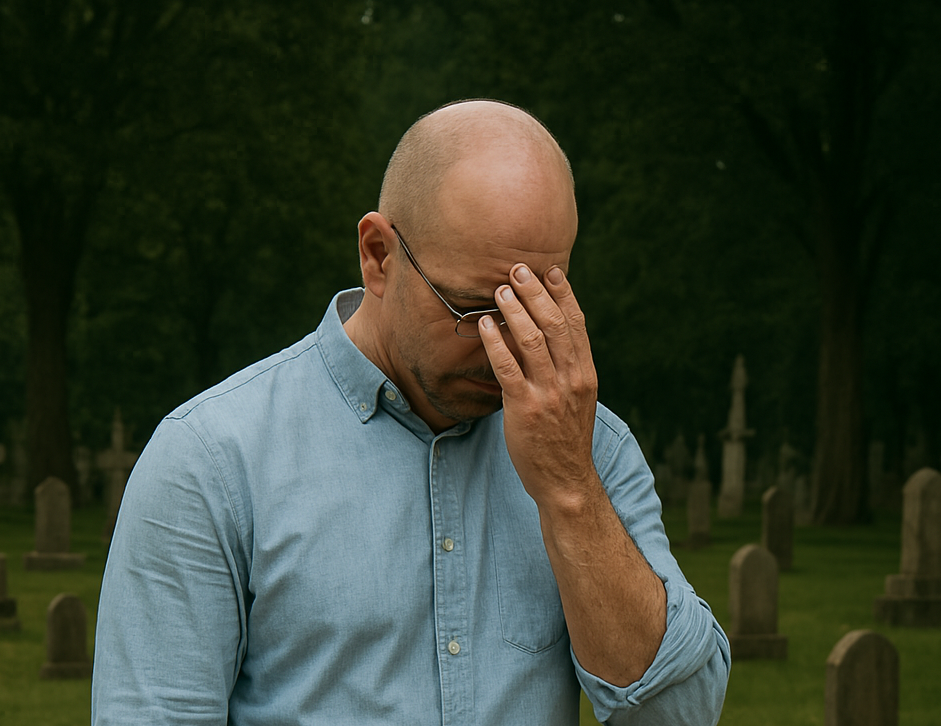

Holding Enoch’s Hand: A Father’s Grief and the God Who Absorbs Our Pain

I held my son Enoch’s little hand as he died. No words can contain that suffering. A heart perpetually wounded, refusing to mend. A body broken beyond any earthly remedy. A home shattered, its foundations irreparably cracked. In the wake of such loss, the questions come like waves, relentless and consuming: Will I see my son again? Is there any justification—any theodicy—that could possibly suffice? Is evil merely a sociological phenomenon, or something far deeper? What unexamined philosophical assumptions lurk beneath our very framing of the question? And how does the blood-stained cross of Jesus of Nazareth speak to this universal agony?

But go to [God] when your need is desperate, when all other help is vain, and what do you find? A door slammed in your face, and a sound of bolting and double bolting on the inside. After that, silence.”

― C.S. Lewis, A Grief Observed

There are more books, more debates, more hollow platitudes about suffering than perhaps any other subject in theology. But when grief is this personal, we do not need complexity—we need truth. Raw, unflinching truth. So let me share with you seven hard-won convictions, forged in the furnace of loss.

First: Evil’s Existence Presupposes God

A friend once told me that if his child died, he would abandon faith. Become an atheist. But here is the devastating irony: You cannot even speak of evil without smuggling in God.

Evil is a deviation from the way things ought to be. But “ought” implies a design. A design implies a Designer. To decry suffering as wrong is to invoke an absolute standard—one that cannot exist in a godless universe of mere particles and chance. My friend, in his rage against the heavens, was borrowing from the very divine order he sought to deny.

Atheism cannot sustain the concept of evil. Nihilism swallows it whole. If there is no God, there is no “wrong,” only molecules rearranging themselves. But we know—deep in our bones—that a child’s death is not just tragic. It is an offense against the way things should be. And that knowing points beyond this world.

So I say to my grieving friend: Do not flee from the One who gives the standard by which you cry out. Cling to Him. For in Him alone is there a peace that surpases understanding—something far greater than mere answers.

Second: The Logical and Evidential Problems of Evil—Are Defeated

Philosophers divide the moral problem of evil into two categories:

The Logical Problem – Can evil coexist with an all-powerful, all-good God?

The Evidential Problem – Does the amount and kind of evil we see count against God’s existence?

Augustine, Aquinas, Plantinga, and Swinburne dismantled the logical problem.

Plantinga’s Free Will Defense demonstrated that a world with free creatures capable of love is logically better than a world of pre-programmed automatons. For love to be real, rejection must be possible. Thus, evil is not proof against God’s existence, but a tragic necessity of a greater good: creatures who can choose Him.

As for the evidential problem—doesn’t the sheer amount of suffering count against God?—Swinburne and others argue that certain goods (courage, compassion, redemption) require suffering. A world without pain would be a world without heroes, martyrs, or the cross.

Yet none of this erases the scream of a grieving father. I do not have a syllogism to soften Enoch’s absence. But I have this: God did not exempt Himself from the suffering He permits.

Third: Evil is not Absolute– The Closer to the Son, the Fewer the Shadows

When a child complains after her mother shut off the light for her bedtime, “Mamma you brought darkness into my room!”—But she did not bring darkness. She merely removed the light.

Evil is like that. It is not a substance, but an absence. A corruption of what should be. There can be absolute Good (God Himself), but no “absolute Evil,” for evil is parasitic, a twisting of the good. Augustine’s answer was radical: Evil has no ontological status. It is not a “thing” but a privation—a corruption of the good, like rust on iron or rot in wood. Evil is parasitic; it exists only by distorting what is real and good. Just as darkness is the absence of light, evil is the absence of God’s order.

Furthermore, atheism has no ground to call anything objectively evil. Pantheism dismisses it as an illusion. But we know—rape, genocide, the slow suffocation of a child’s lungs—these are not illusions. They are horrors. And they make sense only in a world that has strayed from its Source.

The farther a planet is from the sun, the colder and darker it becomes. So too with your soul when it moves away from the Son. Enoch’s death plunged me into a frigid night. I could not see God. But he always saw me. But I have learned this: The closer I press to the Son, the more the shadows retreat. For in Him, there is no darkness at all.

Fourth: Not All Evil Is Sin—God Redeems It All

Enoch’s death was evil—but not sin. There was no moral fault in his tiny body failing.

Sin is the willful defiance of God’s law (1 John 3:4). But earthquakes, cancer, a surgeon’s tragic error—these are evils, yet not sins. R.C. Sproul was right: “Evil is not good, but it is good that there is evil.” A bold claim—yet Scripture whispers it too. Joseph’s betrayal. The cross itself. Aquinas and Augustine both argued that:

Since God is the highest good, He would not permit any evil to exist in His works unless His omnipotence and goodness were such as to bring good even out of evil.’” (Summa Theologica I.2.3).

The distinction between moral evil (sin) and natural evil (suffering) is ontologically and theologically critical. Sin, as a willful violation of divine law (1 John 3:4), requires moral agency, whereas natural evils—disease, disasters, or accidental harm—are non-volitional corruptions of creation’s original goodness. Following Augustine and Aquinas, these latter evils lack moral culpability but retain teleological purpose: God permits them only insofar as He sovereignly ordains their redemption into greater goods (Summa Theologica I.2.3). This is not theodicical evasion but metaphysical necessity—for if God is both omnipotent and wholly good, then evil cannot be ultimate. It must serve, however mysteriously, a higher good that could not be achieved otherwise (as in Joseph’s betrayal culminating in Israel’s salvation, or the cross transforming cosmic rebellion into redemption).

And in my life? From Enoch’s ashes arose two miracles: Daniel and Ana, adopted from Moldova’s poverty. Their laughter does not replace his absence. But it is a foretaste of redemption.

Fifth: Suffering Is Not the Enemy We Think It Is

*”I walked a mile with Pleasure…

She chatted all the way,

But left me none the wiser

For all she had to say.

I walked a mile with Sorrow…

And ne’er a word said she;

But oh, the things I learned from her

When Sorrow walked with me.”*

—Robert Browning Hamilton

Paul, shackled in prison, penned epistles that would shape civilizations. Lincoln, bearing the weight of a fractured nation, became the emancipator. Luther, staring down the wrath of empires, recovered the gospel.

The pattern is inescapable: Great souls are forged in fire. This is not mere poetic sentiment but a psychological and spiritual law written into the fabric of existence. Suffering operates as a ruthless but necessary sculptor—stripping away the fragile veneer of self-sufficiency, exposing the illusions we mistake for strength (“When I am weak, then I am strong” – 2 Cor. 12:10). The poem’s contrast between Pleasure (chatty but empty) and Sorrow (silent but transformative) reveals a paradox: what we instinctively avoid (pain) is often the very thing that initiates us into wisdom. Modern psychology confirms this—post-traumatic growth is well-documented, yet it requires something faith alone can provide: the assurance that suffering is not meaningless.

In my grief, I discovered a brutal but sacred truth: Suffering is the chisel that shapes saints, but it is also the mirror that reveals our idols. When Enoch died, every trivial comfort I’d clung to—reputation, intellectual certainty, even religious routine—collapsed like straw. What remained? Only the bare, terrifying, and liberating reality of God Himself. This is the psychological comfort hidden within the challenge: Suffering does not merely destroy; it unmasks. It shows us what we’ve loved more than God, and in that awful clarity, offers us a choice: Will we rage against the chisel, or surrender to the Sculptor?

Where was God when Enoch died? Was He indifferent? Cruel? Powerless? I’ve raged at the heavens, wept until my body gave out, and felt the crushing weight of a world that offers no real answers. Fatalism tells me I’m helpless. Karma mocks me with the lie that I deserved this. Secularism shrugs and says Enoch’s life—and my pain—are meaningless. But the cross of Christ roars back: This was not random. This was not punishment. This is not the end.

God watched His own Son die—so He knows my agony. He wept at Lazarus’ grave—so He has counted every one of my tears. He split open the tomb, so Enoch’s breath will return to his lungs. But here’s the question that claws at me in the night: Will I let this loss drive me into God, like a nail piercing flesh, anchoring me to Him—or will I let it sever me from His presence?

This was and still is my choice: To let grief make me bitter or to let it break me open. To collapse into despair or to rise in defiant trust. Because if I cling to Him—when I cling to Him–this pain will forge in me a faith that hell cannot shake. Enoch’s life was sacred. My suffering is being woven into something eternal. But I must choose to believe it, even when every breath feels like a battle.

The saints of history chose the battle, not because they felt no pain, but because they trusted the hands that held them. And here lies the personal provocation: If we avoid suffering at all costs, we may be avoiding the very thing designed to make us whole. To run from the fire is to remain unrefined; to endure it, clinging to Christ, is to emerge—like Job, like Paul, like Enoch’s father—with something far greater than answers: a face-to-face encounter with the God whose own nail-scarred wounds–heal.

Suffering strips away illusions. It is the chisel that shapes your soul into something glorious.

Sixth: That must be God on the Cross or Evil remains Unanswered

Here is the unyielding truth: If Jesus was not fully God and fully man on the cross, then evil has not been answered.

He had to be fully man to bear human sin, to suffer as we suffer, to die our death.

He had to be fully God to absorb the infinite wrath of divine justice and still rise.

The early Church fought heresies (Arianism, Docetism) that denied Christ’s divinity or humanity. Why? Because if He was not both, our salvation collapses. Christ must be fully God, or His suffering lacks infinite worth. As Athanasius declared, ‘For the Son of God became man so that we might become God’ (On the Incarnation 54)—but if He were not divine, His death could not shatter death’s dominion. Only the Uncreated can bear the weight of eternal justice. Yet He also must be fully man, or His suffering is illusory. Gregory of Nazianzus thundered, ‘What has not been assumed has not been healed’ (Epistle 101)—if Christ did not truly take on human frailty, grief, and mortality, then His agony in Gethsemane is theater, His cry of dereliction a lie. A half-God cannot save; a phantom cannot bleed.

Here’s the razor’s edge: If Christ’s divinity is diluted, His sacrifice is insufficient; if His humanity is diminished, His solidarity with us is fraudulent. This is why the early church fought so fiercely against Docetism and Arianism—because a Savior who does not fully enter our suffering cannot fully redeem it. Your pain, your doubt, your rage—He absorbed them all, not as a distant deity waving a wand, but as a man of sorrows, acquainted with grief (Isaiah 53:3). The mystery is this: Only the God-man can bridge the chasm between heaven’s holiness and hell’s despair—and He did it with nail-scarred hands

As philosopher Peter Kreeft wrote:

“There is one good reason for not believing in God: evil. And God himself has answered this objection not in words but in deeds and in tears. Jesus is the tears of God. If that is not God there on the cross but only a good man, then God is not on the hook, on the cross, in our suffering. And if God is not on the hook, then God is not off the hook. How could he sit there in heaven and ignore our tears?” (Making Sense out of Suffering, IVP, 1986)

People say they understand my pain. They can not. But God does—because on the cross, He drank the cup of every human agony. And His resurrection shouts: Death is not the end.

Seventh: Evil Is Not “Their” Problem—It Is Ours

The Church has failed often. But she has also done more to alleviate suffering than any institution in history.

Yet we must ask: How much evil persists because I did nothing?

The world, they say, is a tapestry woven with threads of joy and sorrow. But when the thread of your own child is violently severed, the remaining fabric feels irrevocably torn, a gaping wound where vibrant color once resided. The platitudes of comfort ring hollow; the easy answers crumble into dust. In the face of such profound loss, the comfortable distance we once maintained from the world’s suffering vanishes, replaced by a raw, visceral understanding of its brutal reality.

For me, the death of my son was not just a personal tragedy; it was a brutal awakening. The comfortable illusion that evil was “out there,” a shadowy force separate from my own life, shattered into a million pieces. The question that now haunts my waking hours is not just why this happened, but how much darkness persists because I did nothing to push back against the encroaching shadows before they reached my own door?

James 4:17, once a verse to ponder, now pierces my soul like a shard of glass: “So whoever knows the right thing to do and fails to do it, for him it is sin.” The weight of this truth is crushing. Did I, in my relative comfort, become complacent? Did I turn a blind eye to the suffering that festered in the periphery, believing it would never touch my own life? My son’s absence is a stark and agonizing reminder that evil is not a distant concept; it is a pervasive force that thrives in the silence and inaction of those who could, and should, stand against it.

My son’s suffering and death diminish not just my world, but the collective human experience. To have stood by while darkness gathered, even unknowingly, feels like a profound failure of our shared responsibility. Burke’s chilling words resonate with a newfound and agonizing clarity: “The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.” My inaction, however unintentional, allowed the shadows to lengthen, eventually engulfing the light of my son’s life.

The call to be Christ’s hands and feet takes on a desperate urgency. My hands feel numb, my feet heavy with grief. But the question echoes relentlessly: if I do not act now, in the face of this unimaginable loss, who will? My son’s death cannot be in vain. It must become the catalyst for a fierce and unwavering commitment to confront the evil that permeates our world. The Good Samaritan did not cross the road; he was moved with compassion and acted. My grief must transform into that same radical compassion, compelling me to reach out to others drowning in their own personal hells.

My inaction before now feels like a profound dereliction. The hungry I could have fed, the lonely I could have comforted – these now take on a sharper, more agonizing edge. For in a world where such suffering exists unchecked, the potential for unimaginable loss looms large for every parent, every loved one. My son’s death has stripped away my naivete, revealing the urgent need for tangible action against the forces of darkness.

Like Basil the Great, who saw the suffering of his time and responded with radical charity, I build a ministry of hope amidst despair. Like Augustine grappling with the reality of evil, I am confronting the darkness with the unwavering light of truth–not my truth– His Truth. Like Francis of Assisi, embracing the marginalized, I reach out to those in their deepest pain. Like Mother Teresa finding Christ in the broken, I must seek to elevate the suffering of others, not to diminish their pain, but to walk alongside them and illuminate the path toward hope and healing. Although I am not 1./2 the person they are, I must try.

My son’s death has become the unlikely genesis of my apologetics ministry. It is born not from abstract theological debate, but from the raw, agonizing cry of a father’s heart. I will dedicate myself to helping others find evidence for their faith, not in sterile arguments, but in the midst of their own personal hells, where doubt and despair threaten to consume them.

But this ministry will also be a flame, burning away the lies and distortions that allow evil to thrive. It will seek to expose what should not be there – the injustices, the oppressions, the indifference that create fertile ground for suffering. And in that burning away, I pray that the true gold of the soul – resilience, faith, hope, and love – will emerge, refined and strengthened in the face of adversity.

My hands may forever bear the invisible scars of this loss, but they will not remain idle. My feet, though heavy with grief, will walk the difficult paths toward justice and compassion. My son’s memory will not be a source of endless despair, but a wellspring of fierce determination. I will become the bloody hands and weary feet of Jesus to those who are hurting, to those who are lost in the darkness, so that perhaps, through the ashes of my own personal hell, a flicker of God’s light can ignite hope in the hearts of others. My son’s life, though tragically short, will now fuel a lifelong commitment to push back against the darkness, to ensure that no other parent has to ask the agonizing question: How much evil persisted because I did nothing?

How much evil and suffering thrive in your own neighbour or home while you do nothing?

We are Christ’s hands and feet. If we do not act, who will?

The Final Word

Dostoevsky’s Ivan, the tormented atheist, confesses:

“I believe like a child that suffering will be healed and made up for, that all the humiliating absurdity of human contradictions will vanish like a pitiful mirage, like the despicable fabrication of the impotent and infinitely small Euclidean mind of man, that in the world’s finale, at the moment of eternal harmony, something so precious will come to pass that it will suffice for all hearts, for the comforting of all resentments, for the atonement of all the crimes of humanity, of all the blood that they’ve shed; that it will make it not only possible to forgive but to justify all that has happened.” –Fydor Dostoevski’s, Te Brotherd Karamazov (Chapter 3 of Book 5, titled “The Brothers Make Friends”.)

I do not merely dream this. I trust it—because I trust the One whose hands were pierced for me. One day, I will walk with Enoch on the streets of gold, and God Himself will wipe away every tear.

Then I saw “a new heaven and a new earth,”[a] for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and there was no longer any sea. 2 I saw the Holy City, the new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride beautifully dressed for her husband. And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying, “Look! God’s dwelling place is now among the people, and he will dwell with them. They will be his people, and God himself will be with them and be their God. 4 ‘He will wipe every tear from their eyes. There will be no more death’ or mourning or crying or pain, for the old order of things has passed away.” (Revelation 21)

Until then, I wait. And I hold to the promise—not with the certainty of sight, but with the fiercer certainty of faith.

Khaldoun Sweis is Tutor in Philosophy of Religion at Oxford University and Associate Professor of Philosophy at Olive-Harvey College in Chicago. He blogs at logicallyfaithful.com