What is the truth?

In the first century AD, Jesus of Nazareth was taken before Pontius Pilate, the fifth governor of the Roman province of Judaea, serving under Emperor Tiberius from 26/27 to 36/37 CE for crimes against the state. Pilate said that “I find nothing wrong with this man” (Luke 23:4), but because of popular opinion he had him crucified and killed nevertheless. Before he did that, Pilate asked him the infamous question (John 18:38) “What is truth?”, not realizing that Jesus himself claimed to be the truth incarnate. What is the truth? This question has been deliberated more since the turn of the twentieth century than almost at any other previous time. In this video, I go through the concept of objective truth and give an assessment of it.

Two men were confined to a hospital room due to their illnesses. One man had to lie on his back at all times; the other had to sit up for one hour every day because of the accumulation of fluid in his lungs. His bed was next to the only window in the room.

Each day for one hour, he would describe to the man in the hospital bed what he saw out the window. The man in bed began to live for that hour; his roommate spoke of the beautiful lake down below, describing the fishermen and the results of their efforts. Another day he described the skyline of the city on the horizon and the busy lives of the people living there. Mountains in the distance, capped with snow were reported on other days. And so, the months and seasons passed with these two men.

Eventually, the man confined to his back began to resent the reports from the window. He was ashamed to admit it to himself, but it didn’t seem fair that his roommate had a window by his bed. In time, this resentment turned to anger, and then bitterness. One night he was awakened by the coughing of the man next to him, desperately needing to clear his lungs. He looked over and saw him stretching to reach the call button for the nurse. It would have been easy to push his own call button, but he didn’t. He chose to offer no help, and in a few moments the coughing ended. It was replaced with labored wheezing, and finally . . . silence.

A few hours later the nurse discovered that the patient by the window had died during the night. His body was removed from the room and the other man said quietly, “Since I am now alone in this room, may I have my bed moved where I can look out the window?”

The nurse agreed, and after the bed had been moved and he was alone in the room again, he summoned all his strength to pull himself up on his elbows. At last, he would see all that awaited him outside his window.

It was then that he made the discovery— outside the window, there was nothing except a brick wall.

From G.W. Target’s short story written in 1973 called “The Window.”

How can we know that what we hear from the prophets and leaders and ancient books we read is really the story of reality or a brick wall, spiritually speaking? Now, how can we judge the guilt of this man and, the overwhelming guilt he must have for being involved in the death of this man, if there is no theory of justice in this world that is true? What is truth anyway?

In the first century AD, Jesus of Nazareth was taken before Pontius Pilate, the fifth governor of the Roman province of Judaea, serving under Emperor Tiberius from 26/27 to 36/37 CE for crimes against the state. Pilate said that “I find nothing wrong with this man” (Luke 23:4), but because of popular opinion he had him crucified and killed, nevertheless. Before he did that, Pilate asked him the infamous question (John 18:38) “What is truth?”, not realizing Jesus himself claimed to be the truth incarnate. What is truth? This question has been deliberated more since the turn of the twentieth century than almost any other previous time.

There are different theories of truth. What is Truth?

Well, there are many, but here is a preview.

Pragmatic Theory: Truth is that which is practical or makes a difference in our lives

Coherence Theory: Truth is that which makes sense to us and our culture.

Majority Theory: Truth is that which the vast majority of people believe.

Correspondence Theory: Truth is that which corresponds to reality

Relative Theory: There is no truth, objectively speaking

In logic, there are many theories of what is truth, for now here are two.

Every proposition is true or false. [Law of the Excluded Middle.]

No proposition is both true and false. [Law of Non-contradiction.]

The philosophical literature has many books on the issue.

See

1. Blackburn, Simon and Simmons, Keith (eds.), Truth, Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1999

2. The Nature of Truth, M. P. Lynch (ed.), Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 723–749.2001b.

3. Burgess, Alexis G. and Burgess, John P. (eds.), Truth, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011,

4. Kirkham, Richard L., Theories of Truth: A Critical Introduction, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 1992.

5. Künne, Wolfgang, 2003, Conceptions of Truth, Oxford: Clarendon Press.1992.

Many people from a relativistic point of view argue that “It is true that there is no truth” is known as relativism, not relativity, per Einstein, and thus truth has to be addressed in a variety of ways.

Relativism is the view that there is no truth independent of human views. This is false on so many levels. But, why is there is always a but? See below.

The pantheistic worldview, or new age worldview, holds that all reality is one. Therefore, there is no up or down, bad or good, god or man, all is one. Therefore, there is no one truth for all, because all diversity or division is an illusion.

This is the position that many Eastern and New Age mystics advocate. But the relativism of truth is a contradiction. If there are two exact ideas, statements, or features of a situation that are opposed to one another, both cannot be right. So then to say “it is true that there is no truth” is a contradiction and thus, necessarily false. It is false because if there is no truth, then what these relativistic thinkers argue is not true. However, they believe it to be true, otherwise why would they teach it? It’s similar to what is termed the liar paradox. For example, “This very sentence expresses a false proposition” or “I cannot write a word of English.” This is clearly false, as you are reading it.

The basic problem with this, among other things, is the root of the argument. Relativism is a position that most people in pop culture assume by default. It is the position that “No one, and nothing is wrong, it’s just what you wish that thing to be.” It is the unproven assumption that there are no such things as right and wrong in life. But when these relativists reprimand others, saying it is wrong to tell people who do things “differently” wrong, they are doing exactly what they tell others not to do. Do you see a problem here? The people who say it is wrong to say “anything is wrong” are calling those who do believe something is wrong-wrong, wrong! A major contradiction in terms.

The great apologist Ravi Zacharias (March 26, 1946 May 19, 2020) provides the bus illustration to show that the both/and theory of truth is not logical. When you are crossing the street it’s either you or the bus – not both of you! To operate in this world you must have basic truths of gravity, consistent laws, mathematical constants and some sort of code to living. Every axiom assumes some truth value.

The problem with what Ravi mentions, the “law of non-contradiction”, otherwise known as “either-or” logic or the correspondence theory of truth, is that it is black and white, when the world we know is not. What we may see as an oasis in the desert may be a mirage – we find these mirages in our marriage, work and ethical and spiritual life as well.

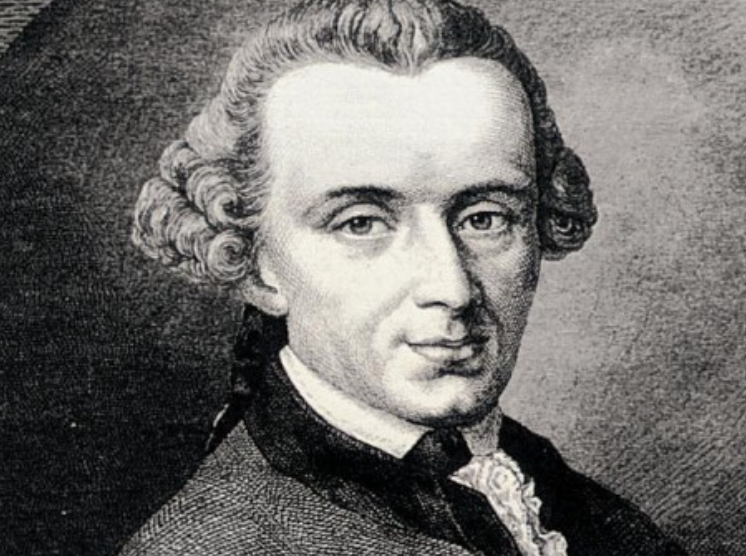

Consider the “the noumenon” Greek: νoούμενον, mentioned by Immanuel Kant in his Critique of Pure Reason (1781). It is the idea that true reality is beyond our grasp. We cannot, let me repeat, cannot see things as independently of human sense and/or perception. The noumenon can be understood in contrast with, or in relation to, the phenomenological events of life. These are the things we experience: cans of soup, your dog, the USSR Flag, etc. Phenomenological refers to anything that can be apprehended by or is an object of the senses.

For Kant it is the “thing in itself” the “truth” or in German, the Ding an sich that is beyond us. All we have is our perceptions—and they are limited, thus so is our understanding of the world.

This is not to say that when you cross the street and a bus is moving at you at 100s of MPH that you will conclude, “Well I don’t know if that really is a bus, since I cannot see the truth,” you will be dead meat, literally as the firemen or paramedics peel your senseless lifeless body from the concrete!

“A priori” and “a posteriori” refer primarily to how, or on what basis, a proposition might be known. In general terms, a proposition is knowable a priori if it is knowable independently of experience, while a posteriori if it is knowable on the basis of experience.

Without any overriding evidence to the contrary, we can assume that what we perceive is in fact the truth. Unless I have a defeater belief, that is, evidence to the contrary, I can assume what I sense to be true. If the baker makes me a strawberry cheesecake and hands me a slice and it looks like strawberry cheesecake, tastes like strawberry cheesecake, feels like strawberry cheesecake, smells like strawberry cheesecake, my senses are clear and healthy, and the baker is an honest man, overall, then I can safely and logically assume that I am buying a strawberry cheesecake, not a python!

However, inside the strawberry cheesecake, unless you are a baker or cook, unlike me, you don’t know the first thing about how to mix properly the following ingredients, 3 8-oz. blocks cream cheese softened 1 c. sugar, 3 large eggs, 1/4 c. sour cream, 1 tsp. pure vanilla extract, 1 tsp. lemon zest, 15 graham crackers, crushed, 5 tbsp. butter, melted, 2 tbsp. sugar, a pinch of kosher salt, 1 c. strawberry preserves, 2 tsp. water (or lemon juice) (From https://www.delish.com/cooking/recipe-ideas/recipes/a52465/strawberry-cheesecake-recipe/ )

But let’s break down at least three of these —wait, yes this has something to do with the topic of truth, just hold your horses.

For pure vanilla extract has the following properties: Natural vanillin (4-hydroxy-3-methozybenazaldehyde), produced from the vanilla bean, and the molecular formula C8H8O3. It is a phenolic aldehyde. Its functional groups include aldehyde, hydroxyl, and ether.

We can go even further, into the chemical properties of aldehyde, hydroxyl, and ether, but I won’t.

Now our brains don’t produce an image the way the digital video camera on our iPhone does. Instead, the mind (which is not the same as the brain) reconstructs a vision of the world from the data provided by units that measure light and shade, edges, twists, and so on in our visual field. This is what accounts for blind spots (the small circular area at the back of the retina where the optic nerve enters the eyeball, and which is devoid of rods and cones and is not sensitive to light) that prevent us from seeing everything around us. If we did, we would go into information overload and lose our sanity. So, what we see is a cascade of limited images that we use to form our view of the world – filtered by our unconscious beliefs and blind confirmation biases, much of which we do not know unless they are pointed out to us, giving a limited and potentially false picture of reality.

Jean Piaget, a Swiss psychologist known for his research on child development, worked on the 4 stages of cognitive development in humans. All together, Piaget’s theory of human cognitive development and epistemological view is called “genetic epistemology”. Sensori-Motor Stage, 2. Pre-Operational Stage According to Piaget, this stage occurs from the age of 2 to 7 years. In the preoperational stage, children use symbols to represent words, images, and ideas, which is why children in this stage engage in pretend play. At this stage the child is ego-centered. He really thinks and believes the world does rotate around him and him alone. If he is upset, he throws a fit because he does not understand why the entire world around him does not cry and weep with him over his spilled caramel chocolate ice cream in aisle 3 of his mother’s favorite grocery store. He thinks the world is as he sees it and does not develop an understanding of the other on a deeper level until the next stage of his development. Let this serve as an example that what we think we see of the world, may not be the way the world is on a deep level.

Visually speaking, what looks one way, may be another. Consider why the moon appears much larger than it is and seems to vary in size: it is what is know as an optical illusion.

Our brains don’t produce an image the way a video camera does. Rather, the brain constructs a model of the world from the information provided by modules that measure light and shade, edges, curvature, and so on. This makes it simple for the brain to paint out the blind spot, the area of your retina where the optic nerve joins, which has no sensors. It also compensates for the rapid jerky movements of our eyes called saccades, giving a false picture of steady vision.

The downside of this process is that it makes our eyes easy to fool. TV, films and optical illusions work by misleading the brain about what the eye is seeing. This is also why the moon appears much larger than it is and seems to vary in size.

So we cannot, as Kant would say, have apodeictic (or apodictic) necessary certainty about what we experience through our senses. We cannot know something to be necessarily true of the world, although it may be possible logically in the a priori sense – that is, intuitively true.

The origin of the word comes from Greek apodeiktikós, meaning demonstrative, i.e. incontrovertible, demonstrably true, or certain.

So relativism is false, clearly, but not easily. Rational thought processes help us see that the truth of a thing is never exhausted by what is revealed to us in a single time and space limited frame of reference. Instead, diverse—perhaps even contradictory aspects of it, are revealed from different perspectives and angles. What makes relativism so appealing is the different angles people have on ideas and events in the world. It makes it appear that there is no truth that is true for all people.

As has been shown, there is serious weaknesses with relativism, both logically and pragmatically speaking. There is objective knowledge in the world, although admittedly it’s often very difficult to find. People, especially those who believe very strongly in an ideology, be it socialism, communism, Islam or Christianity, do so from prior belief systems that make them believe that the way they see the world, is in fact the way the world is. When it is a quite a bit more complex than that!

The bottom line is that our knowledge is always conditioned by one’s viewpoint, which is to say, subjective. But that does not mean that we cannot know if a bus is speeding toward us or that our prayers have in fact been answered by God. To say that we are all trapped in our subjective worldviews, is itself an objective statement that contradicts itself—because it’s trapped too.

We started with Jesus and thus we end with him too. He said, “I am the way the truth, and the life” (John 14:6). He made many statements that he believed to be true and wanted his followers to believe were true as well. Jesus said, “Truly, truly, I say to you, unless one is born again, he cannot see the kingdom of God” (John 3:3). Or “Truly, truly, I say to you, he who believes has eternal life” (John 6:47).

Is what Jesus said only true from his point of view? It does not seem to be the case. If what he said was true from an objective source we cannot know, unless he is the objective source God himself. He himself claimed that he was that God. “I am the Alpha and the Omega, the first and the last, the beginning and the end.” (Rev 23:13).

But there is a powerful individual truth, more important than any objective truth.

Soren Kierkegaard, put it this way:

“The existing individual who chooses to pursue the objective way enters upon the entire approximation-process by which it is proposed to bring God to light objectively. But this is in all eternity impossible, because God is a subject, and therefore exists only for subjectivity in inwardness…Christianity … desires that the subject should be infinitely concerned about himself. It is with subjectivity that Christianity is concerned, and it is only in subjectivity that its truth exists, if it exists at all. Objectively, Christianity has absolutely no existence. If the truth happens to be only in a single subject it exists in him alone; and there is greater Christian joy in heaven over this one individual than over universal history or the system.” (Kierkegaard, Søren,1974 – Concluding Unscientific Postscript Princeton: Princeton University Press., 179)

To which many would disagree. All of apologetic history shouts as Luke Skywalker cried in the 1980 classical sci-fi StarWars The Empire Strikes, “NOOOOO! , it cannot be !”

Kierkegaard is wrong, there is ample objective evidence for the claims of the New Testament regarding Jesus Christ, not just historically, but psychologically and archeologically. But the point about the importance of our subjective acceptance of this truth is far more important to us on a personal level.

We cannot know Christ, the creator, through an objective cerebral process of acknowledging he is the messiah. He is known, wants to be known through a pure and passionate subjective relationship that brings joy to its climax.

So it comes down to faith, or trust—your subjective surrender to the One to whom all existence owes its life. But it is NOT blind trust, it is reasonable faith based on objective evidence.

Let me illustrate this with two scenarios.

A woman marries a man because of his great smile, confidence, kindness, and ability to take care of her financially and spiritually. He shows these attitudes and characteristics during his engagement and comes strongly recommended by his family and friends as a man of integrity. She then marries him, as an act of faith based on the evidence of his life before her and others. She loves him and she trusts him because he has spent the last year as a faithful, honest hardworking man who loves her too. So, when he goes away on a business trip where there are multiple beautiful women there, she trusts him not to break his wedding vows. Does she have absolute certainty? No. She has faith. But it is not blind faith. It is reasonable faith in his truthfulness based on evidence.

She cannot have a relationship with him unless she gives herself to him, subjectively – not objectively in the cognitive sense.

Now, imagine for a moment that the situation was slightly different. This woman marries this man with a great smile and is financially able to care for her, who she has been told, and witnessed with her own eyes, has a propensity to have multiple affairs at the same time during her engagement process. He tells her he “struggles with honesty and fidelity.” The man has children with multiple other women he does not support, and she has caught him with at least 3 other girls who are his concubines or modern-day mistresses. He repents and she forgives him. Despite all of this she marries him on faith that he will be faithful to her after they are married. Now this woman has blind faith or another way to put it, stupid faith!

When I trust in Jesus as the savior of my life and the only messiah hope for mankind, I do that on reasonable faith, not blind faith – in his integrity, honesty, the evidence of his miracles and resurrection from the dead, and most of all, the changed lives of those touched by him in history… as well as in my own life.

But that knowledge of the truth is not enough, I have to say “I do” to him, and on faith put my life in his hands. That takes trust and most of all guts!